Sentiment analysis is about the automated extraction of emotions in text by converting it into machine-readable numbers and labels, which can be analysed statistically, or visualised via plots and graphs.

Think of sentiment analysis as taking the emotional temperature of a text. Imagine reading each chapter and asking, ‘Does this feel positive or negative?’

This started in social sciences as a way to study people’s opinions and attitudes. It only became relevant in literary studies in the 21st century, after being neglected in poststructuralist studies before. Importantly, sentiment analysis focuses on exploring the emotional content in the text, not in the reader’s response. For instance, Patrick Colm Hogan’s ‘affective narratology’ proposes that emotions in a story can set its main features and narrative structure.

I will show how I applied sentiment analysis to an epic 18th-century Chinese novel, The Dream of the Red Chamber, consisting of 120 chapters in total.

This novel is about the rise and fall of a big aristocratic family in the Qing dynasty. The narrative traces the life of the family’s male heir, whose name is Baoyu. His interactions with a diverse cast of female friends, relatives, and servants drive the storyline forward. Sinologists usually interpret this novel as a tribute to the multifaceted female characters, which represent women’s diverse lives & psychology in 18th-century China. But I want to offer a contrasting view and contend that the tale revolves around the narrator’s evaluation of the male protagonist. I put forward the hypothesis that the sentiment arc of the whole novel remains closely aligned with the sentiment profile of the male protagonist. This claim proves a relatively confined psychological scope of the novel, which disputes a superficial feminist reading.

Analysis steps

My sentiment analysis followed 4 simple steps, using Python and MS Excel.

- First, I needed to clean the text. When I extracted digitised text from Project Gutenberg database, I removed copyrights notices, disclaimers, and any noise that might interfere with computational analysis.

- Second, I needed to tokenise the text. Tokenisation means breaking down a text into smaller units, usually words, sentences or paragraphs. Once the text is tokenised, the computer can calculate the sentiment score of each word or sentence by giving them a score from very positive to very negative. You can use these individual scores to calculate the overall sentiment of the paragraph, chapter, or entire novel. If you want construct an emotional profile about certain character, you simply need to extract all sentences mentioning the character’s name, and perform sentiment analysis on these sentences.

- Third, I needed to analyse the output. I had a list of sentences with their respective sentiment scores. I did some data manipulations to generate the average sentiment and emotional intensity data per chapter.

- And finally, I needed to visualise my findings in graphics, and interpret these graphics to gather insights.

Find my python code for tokenisation and sentiment score analysis below:

Findings

The sentiment arc allows us to track the evolution of average sentiment score through chapters.

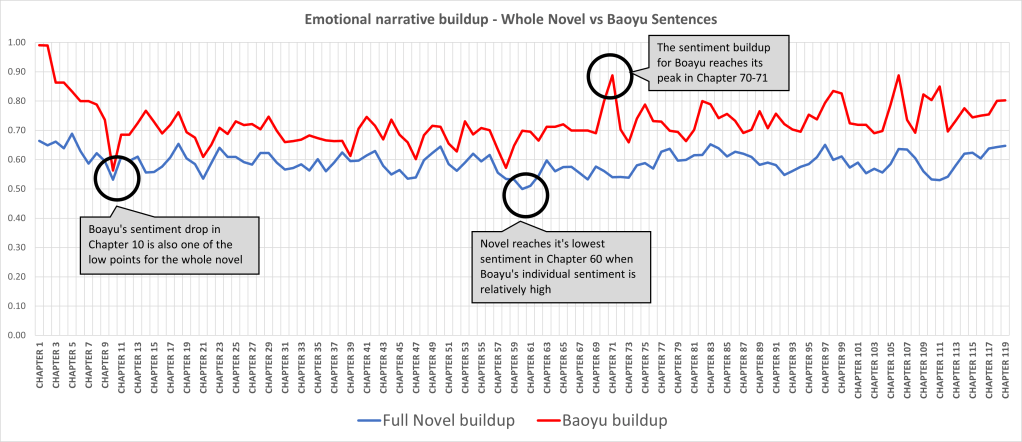

The sentiment arc of the entire novel is the blue line. The sentiment arc of the male protagonist is the red line. If you want to know how to calculate the sentiment score about certain character, you simply have to perform analysis on all the sentences that mention the character’s name.

While these two lines not perfectly aligned, their correlation score of 0.45 shows that a lot of the novel’s emotional tone mirrors Baoyu’s sentiment development. This reveals that the novel has a consistent narratorial focalisation on the male protagonist.

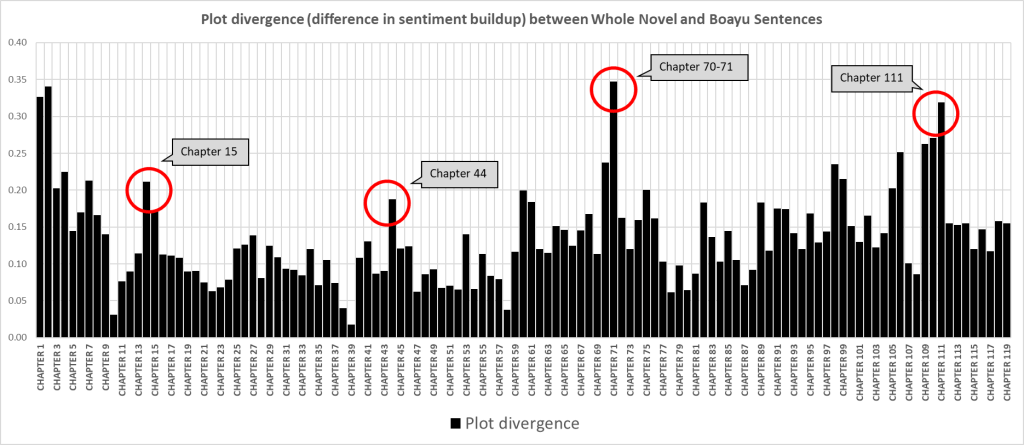

Indeed, there are several points of divergence, such as in chapter 70-71, which guided me back to a close reading to identify possible reason(s) for this divergence. After reading the text, I noticed that, while the chapter’s wider context is about busy family affairs (some characters have fallen ill, while others are busily preparing for funerals), the male protagonist exhibits a strikingly playful demeanor. This can be exemplified by his playful ‘language disorder’ and a palpable sense of ‘erotic ecstasy’, as translated from the Chinese phrase ‘情色若痴,語言常亂’.

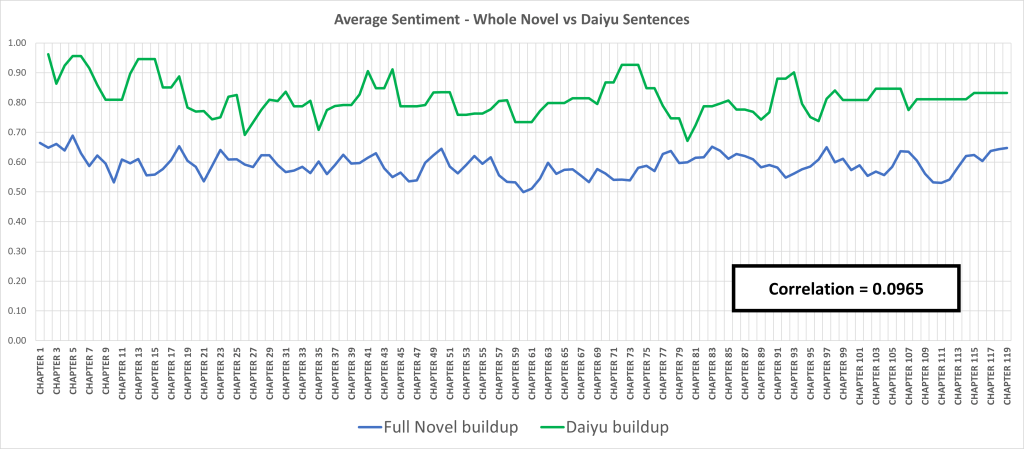

Following the same approach, we can also extract sentiment data about other characters in the novel. For example, Daiyu, one of the central female characters, has a sentiment arc that does not correlate with the novel. This suggests that the narrator’s recounting of speech and events linked to her diverges from the emotional tone of the main storyline.

Another fascinating dimension is the ‘Emotional Intensity’ data. Instead of just determining if feelings are positive or negative, intensity measures the change of sentiment score through chapters; and indicates the magnitude of the change.

In our novel, the overall sentiment had an average intensity of 0.026, suggesting a relatively steady emotional progression. However, when we zoom into the protagonist, his average intensity jumps to 0.042, showing a tumultuous sentiment fluctuation. By comparing these, we can deduce that Baoyu’s appearance brings more dramatic emotional shifts to the novel.

Linking this back to some of my other own research – if I were to adapt The Dream of the Red Chamber into an opera, I would probably want to focus my libretto on Baoyu, because having emotionally intense lyrics is crucial to the success of an opera. Meanwhile, comparing the sentiment profiles of all characters in the novel can help me decide which ones can be made ‘operatic’.

Limitations

My Python analysis utilises the Snow NLP library, which is compatible with the Chinese language. This library is trained on a large dataset of sentences labelled by human as positive or negative. When applied to the novel, it compares specific sentence in the novel against the labelled texts, considering the wordcount of positive and negative terms per sentence and sum their values. Eventually, it assigns a score on a scale ranging from 0-1, indicating the probabilities of each sentence being positive or negative.

This approach simplifies emotions to the two dimensions of positive and negative. But literary work entails emotions that are more complex than this 2D representation.

In addition, to get the sentiment profile of certain character, I focused on sentences directly mentioning his name, but in doing so, I ignore the wider context that also shapes his characterisation.

Moreover, the accuracy of the library directly impacts the precision of the outcome – if the library has been trained on modern language texts, a historical novel like The Dream of the Red Chamber might contain language nuances outside the library’s typical patterns.

Conclusion

It is worth noting that currently, most digital tools focus on the English language, but this article shows how digital methods can enhance our understanding of literature written in another language. We as scholars in modern languages can help decolonise Digital Humanities through innovative teaching and collaborative research. By doing so, we can gradually shift away from digital Anglocentrism and monolingualism toward a more inclusive & comparative approach.

Leave a comment